In accelerated weathering testing, water is often the most difficult factor to accelerate. You cannot make water sit on a panel “faster” in a tester than in the real world. Since many materials outdoors will be wet for 8 to 12 hours a day, an accelerated test in many cases needs to simulate the same deep penetration of water into the material in order to correlate to real world conditions – and this means it has to be wet for a long time.

One way we can accelerate the effects of water is by increasing the temperature of the water. As the temperature increases, the air can hold more water vapor, which allows for increased water absorption into materials. Since condensation is formed from hot water vapor, the temperature of the water is easily controlled and the chamber can reach temperatures up to 60 °C. In contrast, it is difficult to run a water spray step in a Xenon Arc or Fluorescent UV tester while simultaneously maintaining high specimen temperatures, which is why water uptake is more difficult with spray than condensation.

But How “Wet” is a Condensation Step?

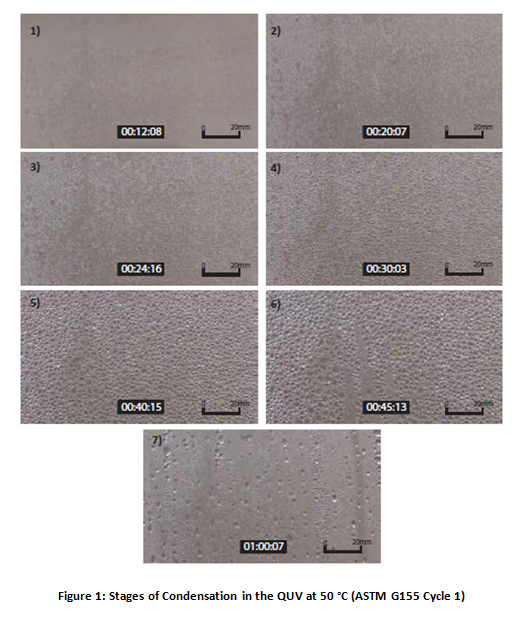

It’s hard to really appreciate how wet a condensation step is because it’s less obvious than looking at water spray. Figure 1 shows a set of seven pictures demonstrating how wet the first hour of a condensation step is.

Once all of the initial droplets have run off the specimen, the cycle repeats with the formation of small droplets, those droplets getting larger, and those large droplets running off of the specimen. At any time 20 minutes or longer into the condensation cycle, the specimens are covered in water, and over the course of four hours, condensation is continually forming and dripping off of the specimens.

Most people would expect that weathering test specimens in a QUV condensation step are exposed to only a small amount of water. In reality, over four hours, a condensation step not only provides almost continuous exposure to aqueous water, but also elevates the temperature of the saturated air, exposing a specimen to a higher amount of water vapor. Unless you’re testing a thick, insulated material, hot condensation in a QUV tester is the best way to accelerate water uptake in a weathering test.

To read more about Q-Lab and to find more articles like this, please visit Q-Lab Blog.